In the dimly lit chambers of Renaissance Europe, a quiet revolution was unfolding not on canvases or in chapels, but in the palms of noblewomen and merchants alike. The pendant, often dismissed as mere ornamentation, emerged as a profound vessel of memory, faith, and identity. These small, intricate containers—crafted from gold, silver, or enamel—were far more than decorative baubles; they were portable repositories of the soul, bridging the earthly and the divine in an age of seismic cultural shift.

The Renaissance pendant was a marvel of duality: both public display and private sanctum. On the surface, it proclaimed wealth and status through exquisite craftsmanship—gems cut to catch the light, filigree work so fine it seemed spun by angels. Yet, within its hidden compartment lay secrets known only to the wearer: a lock of hair from a departed lover, a fragment of scripture, a sliver of saintly relic. This interplay of outer splendor and inner meaning mirrored the era’s broader tensions—between humanism and piety, innovation and tradition.

To understand the pendant’s significance, one must first appreciate the Renaissance obsession with memory. In a world without photographs or digital archives, objects served as tactile anchors to the past. A pendant containing a miniature portrait of a husband away at war became a daily ritual of remembrance; one holding a child’s first curl was a testament to fleeting innocence. These were not passive keepsakes but active participants in the wearer’s emotional life, summoned during prayer, grief, or contemplation.

Faith, too, found a home in these miniature chests. The Catholic Church’s veneration of relics—bones of martyrs, fragments of the True Cross—trickled down from cathedrals to personal devotion. Pendants became micro-reliquaries, allowing believers to carry divine protection close to their hearts. For Protestants, who rejected such practices, pendants might instead hold handwritten Bible verses, asserting a more intimate, unmediated relationship with God. In both cases, the pendant was a tangible expression of spirituality, a shield against the uncertainties of plague, war, and mortality.

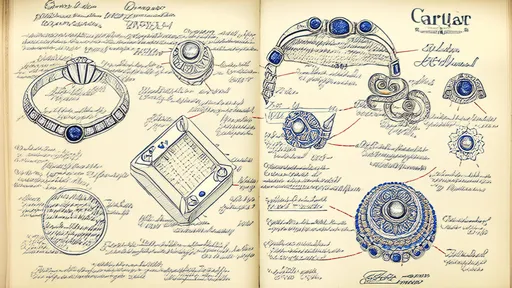

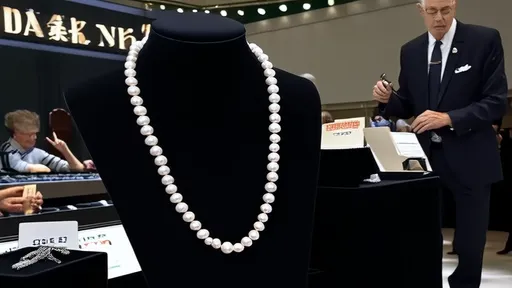

Artisanship reached dizzying heights to meet these demands. Goldsmiths in Florence, Augsburg, and Paris competed to create ever more ingenious designs: pendants that unfolded like altarpieces, others with multiple hidden chambers, some even incorporating clockwork mechanisms. The materials themselves carried symbolism—pearls for purity, rubies for Christ’s blood, enamelwork depicting biblical scenes with microscopic precision. Each piece was a collaboration between artist, patron, and the cultural currents of the day.

Women, in particular, wielded pendants as tools of agency. In societies where their voices were often suppressed, these objects allowed them to curate their narratives. A widow might wear a pendant commemorating her husband not just as grief, but as a claim to his legacy; a queen might use one to display loyalty to a faction or faith. The pendant’s intimacy—worn against the skin, hidden under garments—gave women a rare sphere of control over their identities.

The evolution of pendant designs also mapped geopolitical tides. Italian pendants of the early Renaissance favored classical motifs—cameos of Roman emperors, mythological scenes—reflecting the revival of antiquity. Northern European pieces, by contrast, often leaned into Gothic intricacy and religious fervor. As trade routes expanded, exotic materials like Colombian emeralds or Baltic amber appeared, weaving global connections into personal adornment.

Yet for all their artistry, pendants were never immune to critique. Reformers like John Calvin decried them as vanity, while moralists warned that love tokens could lead to sin. Even supporters acknowledged their power—to distract, to idolize, to deceive. The very qualities that made pendants compelling—their secrecy, their emotional charge—also rendered them ambiguous. A pendant given as a pledge of love might later become evidence of betrayal; one holding a relic could be deemed fraudulent.

By the late Renaissance, the pendant began to shed some of its sacred gravitas. The rise of portraiture miniatures—painted on ivory and set behind crystal—shifted focus from relics to likenesses. Scientific curiosity birthed pendants that held compasses, sundials, or even poisons. The container remained, but its contents increasingly reflected a world turning toward empiricism and self-fashioning.

Today, Renaissance pendants in museum cases often appear as fragile curiosities. But to see them merely as art is to miss their heartbeat. They were, in their essence, negotiations—between public and private, faith and reason, memory and loss. In an age that rediscovered the individual, they offered a way to carry one’s inner world literally on one’s sleeve—or just above one’s heart.

Perhaps their deepest legacy lies in this very human need to externalize the intangible. We still cling to lockets, lock screens displaying loved ones’ faces, amulets for luck. The Renaissance pendant simply did so with unparalleled artistry and existential urgency. It reminds us that the smallest containers can hold the weightiest things: not just hair or text, but hope, identity, and the relentless human desire to make meaning tangible.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025